Behind the Scenes with the Image Makers

2019 Chandra Archive Collection

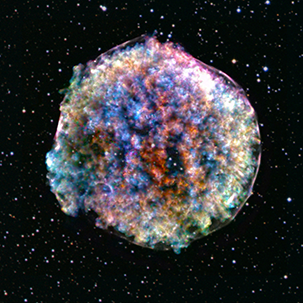

Credit: Enhanced Image by Judy Schmidt (CC BY-NC-SA) based on

images provided courtesy of NASA/CXC/SAO & NASA/STScI.

It is both an art and a science to make images of objects from space. Most astronomical images are composed of light that humans cannot detect with their eyes. Instead, the data from telescopes like NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory are “translated,” so to speak, into a form that we can understand. This process is done following strict guidelines to ensure scientific accuracy while trying to achieve the highest levels of aesthetics possible.

Over the two decades of the Chandra mission, we have had many talented people who have been involved with making our publicly-released images. We interviewed our current team and share some of their answers to questions posed to all of them below. Kim Arcand is Chandra’s visualization lead and has been with the mission since before launch; Nancy Wolk has been involved with Chandra’s data analysis, software, and spacecraft science operations before joining the image processing team; Lisa Frattare spent years making images from the Hubble Space Telescope before switching career gears but continues to lend her expertise part-time to Chandra’s efforts; Judy Schmidt is a citizen scientist who spends some of her free time using public data to make gorgeous images of space, including those featured in our latest release.

How did you get involved in astronomy and/or astronomical images?

Nancy Wolk: I've always wanted to be an astronomer. I studied astronomy and physics in college and completed a Master's degree in astronomy. After graduation, I moved to the Boston area and started working with data analysis with the Chandra X-ray Observatory (then called AXAF). Over the years, I moved from data analysis to software and then space craft science operations. I've been able to talk directly with the observers and help them configure the instruments for them. Most recently, I have been working with preparing images for press releases.

Kim Arcand: I completed my undergraduate work in molecular biology. My interests then were on bacteria and disease, so I was looking at things like Ixodes Scapularis (the Deer tick) and the spirochaetes that can be transmitted to humans which can cause Lyme Disease. But as I neared the end of my degree I found that I was more attracted to the computer as a tool to tell stories about science than I was to any bugs or bacteria. (The physics and chemistry courses I had to take for that degree, however, would become incredibly useful in my later work.) I moved into a computer science graduate program after completing a degree in biology, and the programming/coding/application development of that was a key tool in my future work with Chandra. I would say it was really the mix of science and computer science that helped move me into astronomical data visualization and related projects.

Judy Schmidt: I've long been interested in astronomy, but what got me hooked on image processing was the European Space Agency (ESA) Hubble's Hidden Treasure contest in 2012. Prior to that, I had no idea that data from NASA's Great Observatories are publicly available for anyone in the world to work with. I always wanted to try some astronomical image processing, but I thought I had to buy my own telescope, travel to some dark skies, and capture my own data. Discovering the vast public archives full of professional data changed my life from merely being a casual onlooker to actively participating in a meaningful way within the astronomy community, and I love it.

Lisa Frattare: I have a Master’s in astronomy from Wesleyan University. That landed me working as a data analyst and later, an image processor for the Hubble Space Telescope at Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, MD. I worked on the Hubble Project as a member of the news team and Hubble Heritage Project. My main role was to help astronomers make their scientific data into exciting images that would appeal to fellow scientists and the public alike. During my 20-year tenure at STScI, I worked on over 300 Hubble images, observed with the telescope, worked on 3D imaging of several targets which led to two IMAX films, and did a small stint on processing X-ray data for the Chandra X-ray Observatory. I now work directly with the Chandra news and outreach group. Although X-rays look different than optical data, the mechanism of X-ray data processing is the same. Once again, I convert scientific data into an image that is sometimes rendered as just the X-ray data, and other times it is composited with other wavelengths like optical, infrared and radio.

Do you think working with these images requires particular skills or interests?

Kim Arcand: Being curious about a topic seems to get us pretty far in my group. I would say that curiosity is the most important “skill” in working with data like this. The technical aspects can fall into place with a bit of work, but without that first breath of curiosity, I don’t know how rewarding or interesting it would be for someone. That said, the technical skills are certainly useful to have, though there are a range of different software applications and scripting languages that can help depending on what part of the pipeline of image processing someone is interested in. Some of the astronomical packages like ds9/js9/SAO Image are a good place to start. And Photoshop plus FitsLiberator are an “industry standard.” It certainly never hurts to have coding skills in this area, but I also can’t overstate the usefulness of having an overall aesthetic or “eye” for art as well.

Judy Schmidt: I don't think there is “One True Way,” but a strong familiarity with some kind of digital photo editing software, such as Photoshop, and an understanding of color theory are both essential. My background is in multimedia design, so the astronomy side of things is largely self-taught. This is probably not ideal, but I've managed to make it work. There are a lot of resources available online that I am grateful for, and I have been lucky to sometimes receive some helpful tips directly from professionals. I am also privileged enough in life to have a substantial amount of time available to devote to this hobby.

Lisa Frattare: I don’t think there is a single cookie cutter astronomical image processor. Each of us comes to the role with a different level of interest in science, color, patterns, analytical data, photography, astronomical knowledge, experience, academic training, etc. Part of the equation includes trying something new, putting in the time and effort, and knowing when to stop fussing with an image.

Nancy Wolk: I do find that you need a basic understanding of astronomy and how astronomical images are created. Many times, the images are not projected onto a flat surface, which means you need to be careful doing measurements along the areas with the largest changes from flat. Each telescope is different and aligning the images can be difficult at times. In addition, knowing the physics behind the particular image is important to understanding what you want to emphasize. Basic art skills such as understanding color theory helps as well to choose colors that really make the images catch the public's eye.

Do you think astronomical images resonate with the public in different ways than those from other types of science? If so, why?

Judy Schmidt: Absolutely. Humans have long known that there is something bigger than us out there, and different cultures have so many different stories and metaphors to tell about it, but astronomical images bring us directly in touch with that feeling. It's like making a connection to some secret hidden truth that perhaps we were never worthy of, but the Universe whispered it to us anyway. There's just something special about receiving a message that's thousands, millions, or even billions of years old. And in many cases, it takes little or no special understanding to not only appreciate it, but yearn for more.

Lisa Frattare: There is a feeling of discovery and a sense of wonder that comes from how astronomical images are perceived. From our early photographs of the Moon, to overexposed black and white spirals and ellipticals from early ground-based telescopes, humans have loved viewing and pondering the heavens.

Kim Arcand: I’m a little bit biased here because I come from a place where microscopic images were my first love, and I would like to say they resonate out in the public sphere quite well. I’m also rather loyal to the telescopic images because … well, they’re awesome. So I love the micro and the macro when it comes to imagery. It certainly seems, however (in a non-scientifically assessed way), that the Universe gets more than its fair share of attention with experts and non-experts, and is definitely out in the pop culture world. I’ve found images I or my team have worked on in all sorts of corners of the world, from earrings on Etsy to high-fashion dresses, from album covers to bed covers, in non-astronomy movies and TV/streaming series. It’s always a surprise and a joy to see our data being used in such a way. There’s never enough science imagery for my tastes, but there seems to be a particular appeal to images of the Universe. Perhaps because they seem to hint at answers to those huge questions of where do we come from, who are we, and where are we going?

Nancy Wolk: Many people have a very tenuous relationship with our sky. Living in major cities, many people only see the brightest stars. Bringing people astronomical images really brings the Universe to the people. When we can show images of planets and then some of the more exotic phenomenon in space, we're opening doors of possibility.

Do you have any advice for anyone who is interested in using astronomical data in public archives for image making or other pursuits?

Lisa Frattare: Observational astronomy is a rocking field. Much of the software needed to analyze telescope data is user friendly and meant to be accessed from anywhere. The NASA Great Observatories Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer, put their data in public online archives. Anyone with a computer and a passion can learn how to process images from the archival data to make incredible pictures of the cosmos. There is also a supportive group of interested, non-professional image processors who share and learn from each other.

Nancy Wolk: I've recently had the privilege of working with a young college student in India this past year. We've discussed different ways to process X-ray data so that data are both accurate and pretty. He's asked many questions and I can see how his work has come a long way. I recommend reaching out to the outreach offices at telescopes. That's why we are here. We want to help people hone their skills and learn how to mix the different wavelengths to gain a better understanding of our universe.

Judy Schmidt: Try not to feel intimidated. I used to worry someone would jump in and tell me I was doing everything wrong and bad, but that never happened. Learning the jargon and getting past the technical parts is worth it. Not a whole lot of people do this work, and there's no secret club, so try to find us on Twitter or other social networks. I've helped a lot of beginners who have asked me questions through email, Twitter, and elsewhere.

Kim Arcand: There are so many different ways to try your hand at imaging the Universe. Here is a brief guide of resources we’ve created or partnered on:

- Brand new to this? Start out by learning how computers use red, green and blue to add color to digital images, and try coloring some real NASA data sets at https://chandra.si.edu/code.

- Next, try watching this TEDx talk to get a brief introduction to what we do at Chandra to visualize the high-energy Universe (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8kTMr5LqIBQ). Head over to Vox for a more indepth video on how we color the Universe in different kinds of light (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WSG0MnmUsEY).

- A good next step would be to take an image using the MicroObservatory (https://mo-www.cfa.harvard.edu/MicroObservatory/), where you can even submit an image for their NASA data photo challenges. There are a number of good resources to try in here.

- After that, a trip through our Open Fits tutorials (https://chandra.si.edu/photo/openFITS/) might be a good place to go. "FITS", which stands for Flexible Image Transport System, is a digital file format used mainly by astronomers. In this section you can download FITS files for some of our favorite Chandra images and learn how to compose your own versions of these high-energy astronomy images with a series of short tutorials.

- When you're ready, dive in to the NASA archives! Each NASA mission has a wealth of data to dig through, and such data is typically public about a year after it's been taken. For Chandra, there are about 19 years of X-ray data to comb through for treasures (http://cxc.harvard.edu/cda/). For Hubble, there's about 28 years of data (https://archive.stsci.edu/hst/). And that's just two astronomical missions. All are publicly accessible, ready to be shined up and polished into a gorgeous visual treat.

Category:

- Log in to post comments